Meet Your Neighbor, the Diamondback Rattlesnake

Now that spring is here and summer is upon us, rattlesnakes have become far more active. It is

important for us to become aware of their habitats, and the risks and benefits of living with these

beautiful animals.

About sixty years ago Four Hills Village was built on the western foothills of the Manzano/Manzanita

Mountains, along the southern flank of Tijeras Canyon, a natural source of permanent water (springs)

and a major wildlife corridor. We sit within what is called the Upper Sonoran Climatic (or Bio) Zone, in

the Juniper/Pinon - Juniper vegetation ecozones. That is to say we are in the transition zone between

the high dry desert grasslands and the high cool conifer forests of the mountains. As a result of our

location and the fact that subsequent neighborhood development has preserved many large

interconnected open spaces with access to numerous water sources, we are host to an unusually wide

range of wildlife and vegetation. Snakes are one of the many resident animal groups in FHV.

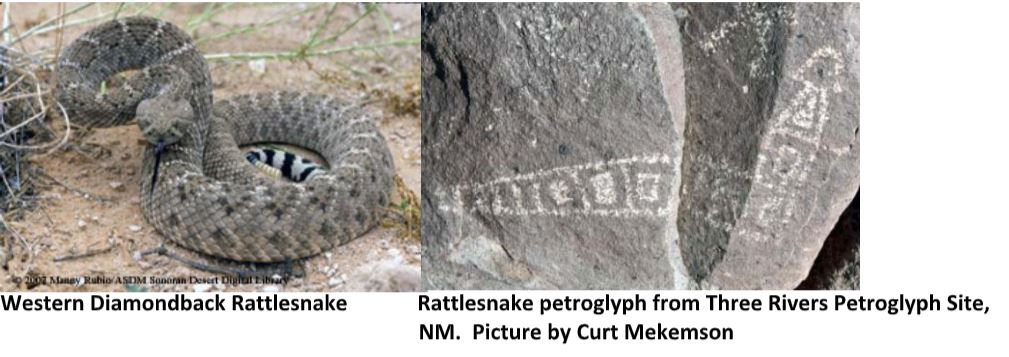

Snakes are thought to have evolved from some yet unidentified land-living lizard in the Late Jurassic

Period (~150 million years ago) and have been in residence in New Mexico for far longer than humans.

They have been vilified and revered. (See picture of rattlesnake petroglyph above), but mostly their role

and value in the ecosystem has been misunderstood.

This note will concentrate on the Western Diamondback Rattlesnake, one of the six most common

snakes in our area. Of our resident snakes, three are nonvenomous: the Bullsnake (also called Gopher

Snake), the Striped Whipsnake, and the Wandering Garter Snake. The other three are all rattlesnake

subspecies: the Prairie Rattlesnake which prefers open or slightly wooded grasslands in the lower

elevations; the Blacktail Rattlesnake, somewhat less common and prefers south facing exposures at the

higher elevations, and the Western Diamondback Rattlesnake (also called Coontail Rattler) which occurs

in high densities all along the western mountain foothills and in our area.

Before you get all jumpy about snakes in our neighborhood, take note that all of these snakes are

basically nonaggressive, although they all take a very dim view of being played with, picked up, or

stepped on. Also, they are not active all of the time. All snakes are cold-blooded and as such they

cannot increase their body temperature when it is cold outside. They become torporous or they

“brumate” (a great word for Scrabble that means a condition similar to hibernation) in cooler or cold

weather. They are most active when the temperatures range between 77 0 and 90 0 F. The Western

Diamondback Rattlesnake’s activity pattern changes seasonally. It is most active at dawn and dusk but

will hunt other times of the day. During the summer it will actively hunt at night and will bask on warm

rocky outcrops by day. In the spring and fall it is more likely to be active during the day. The Western

Diamondback brumates between October and early March. Brumation is carried out in a shelter such as

a cave, rock crevice, or an animal burrow. Multiple snakes (even snakes of different species) may

brumate together.

All of our local snakes are ambush predators whose diets are composed primarily rodents and other

small mammals, rounded out with lizards, amphibians, smaller snakes, ground feeding birds, and the

occasional fish or insect. They occupy a very important place in our ecology. Besides being major

controllers of the rodent population, they also help protect us by consuming rodents/small mammals

hosting Hantavirus-, Bubonic Plague-, and Lyme Disease-infected fleas and ticks. One surprising recent

discovery is that snakes also help disperse seeds of grasses and other plants. The rodents they consume

usually have their cheeks stuffed with seeds which can pass harmlessly through the snake’s gut, and in

some cases even germinate, before being deposited in the snake’s feces.

The Western Diamondback Rattlesnake scientific name is “Crotalus atrox” and it’s a member of the viper

family. It is the second largest of the 40+ recognized species of rattlesnakes in North America -coming in

with a length of 4 to 5 ft. (the largest know was 7 ft. long) and a weight of up to 6 pounds. Only the

closely-related Eastern Diamond Rattlesnake is larger. The Western Diamondback is found throughout

the high deserts of the southwestern US and in the northern high deserts of Mexico.

This handsome snake’s body is heavy looking and is usually brown-grey but may also be dusky grey or

pinkish-gray in color. Running along its back are up to 45 diamonds or hexagon-shapes blotches that are

darker brown than the underlying skin color and have dark edges. These markings are bordered by

sandy-yellow lines. The Western Diamondback has a broad triangular head and a set of back-sweeping

white and/or dark diagonal lines can often be seen on each cheek. The belly of the snake is off-white in

color and unmarked. The snake’s tail is marked with 2 to 8 black and white rings much like a raccoon’s

tail (which is the origin of its alternate name, “Coontail Rattler”). The other two rattlesnakes common in

the Sandia and Manzano foothills lack the black and white banding of the tail.

At the tip of tail is the snake’s rattle which is made of stack of pale brown, hardened hollow scales. A

new segment is added to the rattle every time the snake sheds its skin. However, despite what you may

have heard, you cannot count the number of rattle bands to calculate the snake’s age. These hollow

scales are made of keratin, the same material as we have in our fingernails, and just like our fingernails,

they break from time to time. A very old snake may have lost all of its rattle and young rattlesnakes

don’t have rattles. Most, but not all, rattlesnakes will rapidly vibrate their tail when threatened. This

causes the keratin segments to knock against each other, producing a snare drum-like sound that is

amplified by the hollow scales (and used in hundreds of western movie soundtracks to scare us).

Western Diamondback Rattlesnakes are pit vipers, meaning they have organs behind their nostrils and

between their eyes that can sense very tiny changes in temperature. Tracking subtle changes in

temperature is a primary method used in hunting small mammals. Also, unlike many snakes, the

Western Diamondback has very good vision. When hunting, one quick bite delivers enough venom to

kill or incapacitate its small prey. Occasionally, the snake loses its teeth when it strikes. This is only a

temporary hindrance as lost teeth can be replaced multiple times a year. The snake swallows its prey

whole. Typically, it feeds once every two to three weeks but it can survive up to two years without

eating by slowing its metabolism dramatically and living off stored fat reserves.

The Western Diamondback can live 15-20 years or more. They reach sexual maturity at 3 years of age.

Except for mating and brumation, the Western Diamondback tends to be solitary. Mating takes place in

the spring. During this time the male rattlesnakes engage in ritualized fighting. The combatants coil

their bodies around each other holding their heads high off the ground and slug it out in what is called

“combat dancing”.

The female Western Diamondback Rattlesnake is ovoviviparous. This means she has a reproductive

system in which her young develop in eggs within her body over the course of 6 to 7 months. The young

then “hatch” from eggs within her body prior to being born in apparent “live” birth. A typical brood

consists of 8 to 12 young, but cases of broods of up to 25 are known. Born in the late summer or early

fall, the baby snakes are about a foot long and disperse within a few hours of birth to fend for

themselves. Their mortality rate is very high. Primary predators of the Western Diamond Rattlesnake

include; hawks, eagles, owls, coyotes, grey foxes, bobcats, roadrunners, other snakes, lawnmowers,

automobiles, and people who want to make boots, belts, and cans of exotic stew meat for tourists.

Snake Bite Truths

Each year over 45,000 snake bites on humans are reported in the United States. Of these about 8,000

are from venomous snakes and out of this total there are 5-12 human deaths per year attributed to

snake bite. A significant number of the snake bites occur when people provoke the snake by trying to

handle, capture, or kill it. The Western Diamondback is considered the most aggressive rattlesnake

species and is responsible for the highest annual number of snake bites (but not fatalities) in the U.S.

This is due to the (relatively) low potency of its venom. The Eastern Diamondback’s venom is far more

powerful and it is responsible for more fatalities. The venom from the majority of rattlesnakes is

primarily composed of hemotoxic elements. This means it will damage tissue and affect your circulatory

system by destroying skin tissues and blood cells and cause you to hemorrhage internally. It is

important to remember that a snake’s bite reflex can still be triggered several hours after the animal’s

death and that even a newly born baby rattlesnake can give a venomous bite.

Rattlesnakes, like all vipers, have a pair of hollow retractable fangs positioned at the front of their

mouths. The snake’s venom, which is produced by glands behind their eyes, is injected into the snake’s

prey via these fangs. Although the Western Diamondback’s venom is less toxic than that of many other

rattlesnakes it can be delivered in higher quantities per bite. If left untreated, the bite of the Western

Diamondback venom is potentially fatal to humans (especially to those weighing less than 100 pounds).

However, because the snake rarely delivers a full venom strike (around 25-30% of all snake bites are dry-

meaning they inject no venom) and because the antivenom is readily available, the bites are rarely fatal.

In fact, more damage to humans is done by fear causing heart attacks and by improperly applied

tourniquets, than the actual deaths from the venom.

If you are bitten, or think you have been bitten, the first and foremost thing to do is to move away from

the snake, as they can strike again. Do not waste time and energy trying to capture or kill the snake.

First, the snake has already had a really bad day, and second, this activity will increase your heartrate

and blood circulation, further speeding the toxin throughout your body. Do try to remember its size,

color, and markings to help medical staff select the correct antivenom. You will start to feel symptoms

immediately and they will worsen over time. Do seek medical help as soon as possible. Call for an

ambulance if you are able to, preferably within 30 minutes. Do stay calm and remember that unlike in

the movies and on TV, rattlesnake bites very, very rarely kill humans and that even if left untreated, the

overall effects of the venom usually take days to develop in a human.

If you have been bitten by a rattlesnake, you may notice 1 or 2 puncture marks made by their large

fangs (nonvenomous snake bites usually have multiple punctures arrayed in a “V” or horseshoe shape).

You will probably experience some pain, tingling, or burning in the area of the bite. This may be

accompanied by some swelling, bruising, or discoloration at the site. Other common symptoms include:

There many common misconceptions about the treatment of rattlesnake bites. Here is how to minimize

your risk (according to Healthline, 2020).

A word about dogs, rattlesnakes and the Albuquerque Open Space rules.

If your dog lives, plays, or accompanies you on hikes where rattlesnakes live, it will come as no surprise

that these snakes are a serious danger to our dogs (and cats). Each year about 300,000 dogs and cats

are bitten by venomous snakes. Already this year there have at least two cases of dogs having been

snake bitten in our Manzano/Four Hills Open Space. Because most dogs are smaller animals with high

heartrates, rattlesnake venom will hit them very quickly and very hard. This danger is one of the several

reasons the City of Albuquerque requires all dogs to be on a leash while in the Open Spaces.

You may have heard of, or have had your dog inoculated with, a rattlesnake vaccine developed by Red

Rock Biologics. But are you aware that there is considerable discussion within the veterinary community

about its effectiveness? This rattlesnake vaccine was developed to protect against the Western

Diamondback Rattlesnake by generating protective antibodies against its venom. According to

Red Rock Biologics, it is not effective against other snakes and dogs should be inoculated at least 30 days

before any exposure to rattlesnakes, with booster shots given every 6 months thereafter. The primary

question being debated is how good is this vaccine actually? Even included in Red Rock Biologics own

information is “safety and efficacy are not proven”.

The vaccine efficacy issue has two parts: 1) No hard evidence has been presented on the consistent

behavior of the vaccine. This could be due to the wide variety of dog body types and the wide varieties

in the amount of snake venom injected, depths of bite, and the bite location on the dog’s body; 2) The

purpose of the vaccine is to reduce the time from re-exposure to venom toxins (a snake bite following

inoculation) to produce antibodies (called memory T-cells). The part that is illogical to a large number of

veterinarians is that, with a snake bite on a small animal, you don’t have a few days for the production

of antibodies. Red Rock Biologics have not demonstrated that the vaccine will stimulate enough

antibodies – and quickly enough to neutralize the venom. “If you do decide to use the vaccine, it’s

important not to develop a false sense of security. Owners need to understand that this vaccine will not

eliminate the need to take the dog for care should he be bitten. It may buy some time to get him to the

veterinarian; then again, it may not. Don’t assume the vaccine will provide any amount of cushion”.

(The Rattlesnake Vaccine for Dogs: Both sides of the Story by Dr. Laci Shaible, 2020)

So, if you have the inclination to let your dog off its leash in the Open Spaces or other wild areas of New

Mexico, remember, that as your dog’s Person, you have the responsibility to look out for their

instinctual behavior. Most city dogs (particularly younger dogs) don’t have “snake training”, but they do

have an insatiable curiosity to checkout basking snakes and will take off with the boundless

enthusiasm/lack of judgement of 2-year-old human hyped on sugar to chase the very same prey as

those hunted by rattlesnakes. The ultimate discussion over prey rights and trespassing can be deadly.

Summary

Rattlesnakes are common in our area. Long an icon of many cultures in the American Southwest, the

rattlesnake and the Western Diamondback in particular, plays an important role in controlling the

rodent population and preventing several nasty diseases from spreading widely. Left on their own they

are reclusive not highly aggressive but, when provoked, will attack quickly and effectively with a

venomous strike. Fortunately for humans the bite is rarely lethal because venom is slower acting than

that of many snakes and it is easily counteracted by a widely available antivenom serum. Full recovery is

common.

important for us to become aware of their habitats, and the risks and benefits of living with these

beautiful animals.

About sixty years ago Four Hills Village was built on the western foothills of the Manzano/Manzanita

Mountains, along the southern flank of Tijeras Canyon, a natural source of permanent water (springs)

and a major wildlife corridor. We sit within what is called the Upper Sonoran Climatic (or Bio) Zone, in

the Juniper/Pinon - Juniper vegetation ecozones. That is to say we are in the transition zone between

the high dry desert grasslands and the high cool conifer forests of the mountains. As a result of our

location and the fact that subsequent neighborhood development has preserved many large

interconnected open spaces with access to numerous water sources, we are host to an unusually wide

range of wildlife and vegetation. Snakes are one of the many resident animal groups in FHV.

Snakes are thought to have evolved from some yet unidentified land-living lizard in the Late Jurassic

Period (~150 million years ago) and have been in residence in New Mexico for far longer than humans.

They have been vilified and revered. (See picture of rattlesnake petroglyph above), but mostly their role

and value in the ecosystem has been misunderstood.

This note will concentrate on the Western Diamondback Rattlesnake, one of the six most common

snakes in our area. Of our resident snakes, three are nonvenomous: the Bullsnake (also called Gopher

Snake), the Striped Whipsnake, and the Wandering Garter Snake. The other three are all rattlesnake

subspecies: the Prairie Rattlesnake which prefers open or slightly wooded grasslands in the lower

elevations; the Blacktail Rattlesnake, somewhat less common and prefers south facing exposures at the

higher elevations, and the Western Diamondback Rattlesnake (also called Coontail Rattler) which occurs

in high densities all along the western mountain foothills and in our area.

Before you get all jumpy about snakes in our neighborhood, take note that all of these snakes are

basically nonaggressive, although they all take a very dim view of being played with, picked up, or

stepped on. Also, they are not active all of the time. All snakes are cold-blooded and as such they

cannot increase their body temperature when it is cold outside. They become torporous or they

“brumate” (a great word for Scrabble that means a condition similar to hibernation) in cooler or cold

weather. They are most active when the temperatures range between 77 0 and 90 0 F. The Western

Diamondback Rattlesnake’s activity pattern changes seasonally. It is most active at dawn and dusk but

will hunt other times of the day. During the summer it will actively hunt at night and will bask on warm

rocky outcrops by day. In the spring and fall it is more likely to be active during the day. The Western

Diamondback brumates between October and early March. Brumation is carried out in a shelter such as

a cave, rock crevice, or an animal burrow. Multiple snakes (even snakes of different species) may

brumate together.

All of our local snakes are ambush predators whose diets are composed primarily rodents and other

small mammals, rounded out with lizards, amphibians, smaller snakes, ground feeding birds, and the

occasional fish or insect. They occupy a very important place in our ecology. Besides being major

controllers of the rodent population, they also help protect us by consuming rodents/small mammals

hosting Hantavirus-, Bubonic Plague-, and Lyme Disease-infected fleas and ticks. One surprising recent

discovery is that snakes also help disperse seeds of grasses and other plants. The rodents they consume

usually have their cheeks stuffed with seeds which can pass harmlessly through the snake’s gut, and in

some cases even germinate, before being deposited in the snake’s feces.

The Western Diamondback Rattlesnake scientific name is “Crotalus atrox” and it’s a member of the viper

family. It is the second largest of the 40+ recognized species of rattlesnakes in North America -coming in

with a length of 4 to 5 ft. (the largest know was 7 ft. long) and a weight of up to 6 pounds. Only the

closely-related Eastern Diamond Rattlesnake is larger. The Western Diamondback is found throughout

the high deserts of the southwestern US and in the northern high deserts of Mexico.

This handsome snake’s body is heavy looking and is usually brown-grey but may also be dusky grey or

pinkish-gray in color. Running along its back are up to 45 diamonds or hexagon-shapes blotches that are

darker brown than the underlying skin color and have dark edges. These markings are bordered by

sandy-yellow lines. The Western Diamondback has a broad triangular head and a set of back-sweeping

white and/or dark diagonal lines can often be seen on each cheek. The belly of the snake is off-white in

color and unmarked. The snake’s tail is marked with 2 to 8 black and white rings much like a raccoon’s

tail (which is the origin of its alternate name, “Coontail Rattler”). The other two rattlesnakes common in

the Sandia and Manzano foothills lack the black and white banding of the tail.

At the tip of tail is the snake’s rattle which is made of stack of pale brown, hardened hollow scales. A

new segment is added to the rattle every time the snake sheds its skin. However, despite what you may

have heard, you cannot count the number of rattle bands to calculate the snake’s age. These hollow

scales are made of keratin, the same material as we have in our fingernails, and just like our fingernails,

they break from time to time. A very old snake may have lost all of its rattle and young rattlesnakes

don’t have rattles. Most, but not all, rattlesnakes will rapidly vibrate their tail when threatened. This

causes the keratin segments to knock against each other, producing a snare drum-like sound that is

amplified by the hollow scales (and used in hundreds of western movie soundtracks to scare us).

Western Diamondback Rattlesnakes are pit vipers, meaning they have organs behind their nostrils and

between their eyes that can sense very tiny changes in temperature. Tracking subtle changes in

temperature is a primary method used in hunting small mammals. Also, unlike many snakes, the

Western Diamondback has very good vision. When hunting, one quick bite delivers enough venom to

kill or incapacitate its small prey. Occasionally, the snake loses its teeth when it strikes. This is only a

temporary hindrance as lost teeth can be replaced multiple times a year. The snake swallows its prey

whole. Typically, it feeds once every two to three weeks but it can survive up to two years without

eating by slowing its metabolism dramatically and living off stored fat reserves.

The Western Diamondback can live 15-20 years or more. They reach sexual maturity at 3 years of age.

Except for mating and brumation, the Western Diamondback tends to be solitary. Mating takes place in

the spring. During this time the male rattlesnakes engage in ritualized fighting. The combatants coil

their bodies around each other holding their heads high off the ground and slug it out in what is called

“combat dancing”.

The female Western Diamondback Rattlesnake is ovoviviparous. This means she has a reproductive

system in which her young develop in eggs within her body over the course of 6 to 7 months. The young

then “hatch” from eggs within her body prior to being born in apparent “live” birth. A typical brood

consists of 8 to 12 young, but cases of broods of up to 25 are known. Born in the late summer or early

fall, the baby snakes are about a foot long and disperse within a few hours of birth to fend for

themselves. Their mortality rate is very high. Primary predators of the Western Diamond Rattlesnake

include; hawks, eagles, owls, coyotes, grey foxes, bobcats, roadrunners, other snakes, lawnmowers,

automobiles, and people who want to make boots, belts, and cans of exotic stew meat for tourists.

Snake Bite Truths

Each year over 45,000 snake bites on humans are reported in the United States. Of these about 8,000

are from venomous snakes and out of this total there are 5-12 human deaths per year attributed to

snake bite. A significant number of the snake bites occur when people provoke the snake by trying to

handle, capture, or kill it. The Western Diamondback is considered the most aggressive rattlesnake

species and is responsible for the highest annual number of snake bites (but not fatalities) in the U.S.

This is due to the (relatively) low potency of its venom. The Eastern Diamondback’s venom is far more

powerful and it is responsible for more fatalities. The venom from the majority of rattlesnakes is

primarily composed of hemotoxic elements. This means it will damage tissue and affect your circulatory

system by destroying skin tissues and blood cells and cause you to hemorrhage internally. It is

important to remember that a snake’s bite reflex can still be triggered several hours after the animal’s

death and that even a newly born baby rattlesnake can give a venomous bite.

Rattlesnakes, like all vipers, have a pair of hollow retractable fangs positioned at the front of their

mouths. The snake’s venom, which is produced by glands behind their eyes, is injected into the snake’s

prey via these fangs. Although the Western Diamondback’s venom is less toxic than that of many other

rattlesnakes it can be delivered in higher quantities per bite. If left untreated, the bite of the Western

Diamondback venom is potentially fatal to humans (especially to those weighing less than 100 pounds).

However, because the snake rarely delivers a full venom strike (around 25-30% of all snake bites are dry-

meaning they inject no venom) and because the antivenom is readily available, the bites are rarely fatal.

In fact, more damage to humans is done by fear causing heart attacks and by improperly applied

tourniquets, than the actual deaths from the venom.

If you are bitten, or think you have been bitten, the first and foremost thing to do is to move away from

the snake, as they can strike again. Do not waste time and energy trying to capture or kill the snake.

First, the snake has already had a really bad day, and second, this activity will increase your heartrate

and blood circulation, further speeding the toxin throughout your body. Do try to remember its size,

color, and markings to help medical staff select the correct antivenom. You will start to feel symptoms

immediately and they will worsen over time. Do seek medical help as soon as possible. Call for an

ambulance if you are able to, preferably within 30 minutes. Do stay calm and remember that unlike in

the movies and on TV, rattlesnake bites very, very rarely kill humans and that even if left untreated, the

overall effects of the venom usually take days to develop in a human.

If you have been bitten by a rattlesnake, you may notice 1 or 2 puncture marks made by their large

fangs (nonvenomous snake bites usually have multiple punctures arrayed in a “V” or horseshoe shape).

You will probably experience some pain, tingling, or burning in the area of the bite. This may be

accompanied by some swelling, bruising, or discoloration at the site. Other common symptoms include:

- Numbness in the face or limbs

- Lightheadedness

- Weakness

- Nausea or vomiting

- Sweating

- Salivating

- Blurred vision

- Difficulty breathing

There many common misconceptions about the treatment of rattlesnake bites. Here is how to minimize

your risk (according to Healthline, 2020).

- Don’t raise the bitten area above the level of your heart. If you do this, your blood containing rattlesnake venom will reach your heart more quickly.

- Stay as still as possible, as movement will increase your blood flow and the venom will circulate faster.

- Remove any tight clothing or jewelry before you start to swell.

- Let the wound bleed, as this may allow some of the venom to be released.

- Don’t wash the wound, as your medical team may be able to use some of the venom from your skin to more quickly identify the correct antivenom.

- Place a clean bandage on the wound.

- Try to remain calm, as anxiety and panic can increase your heart rate which will cause the venom to spread.

- If you begin to experience signs of shock, try to lie down on your back, raise your feet slightly and stay warm.

- Don’t cut the wound, as this doesn’t help and could cause an infection (and as one doctor told me when I was being checked out to carry antivenom where I worked, “you are not a doctor and you don’t know where your veins and arteries are located”.

- Don’t try to suck the venom from the wound, as you then introduce the venom to your mouth as well as introduce the bacteria from your mouth to the wound.

- Don’t use a tourniquet or apply ice or water.

A word about dogs, rattlesnakes and the Albuquerque Open Space rules.

If your dog lives, plays, or accompanies you on hikes where rattlesnakes live, it will come as no surprise

that these snakes are a serious danger to our dogs (and cats). Each year about 300,000 dogs and cats

are bitten by venomous snakes. Already this year there have at least two cases of dogs having been

snake bitten in our Manzano/Four Hills Open Space. Because most dogs are smaller animals with high

heartrates, rattlesnake venom will hit them very quickly and very hard. This danger is one of the several

reasons the City of Albuquerque requires all dogs to be on a leash while in the Open Spaces.

You may have heard of, or have had your dog inoculated with, a rattlesnake vaccine developed by Red

Rock Biologics. But are you aware that there is considerable discussion within the veterinary community

about its effectiveness? This rattlesnake vaccine was developed to protect against the Western

Diamondback Rattlesnake by generating protective antibodies against its venom. According to

Red Rock Biologics, it is not effective against other snakes and dogs should be inoculated at least 30 days

before any exposure to rattlesnakes, with booster shots given every 6 months thereafter. The primary

question being debated is how good is this vaccine actually? Even included in Red Rock Biologics own

information is “safety and efficacy are not proven”.

The vaccine efficacy issue has two parts: 1) No hard evidence has been presented on the consistent

behavior of the vaccine. This could be due to the wide variety of dog body types and the wide varieties

in the amount of snake venom injected, depths of bite, and the bite location on the dog’s body; 2) The

purpose of the vaccine is to reduce the time from re-exposure to venom toxins (a snake bite following

inoculation) to produce antibodies (called memory T-cells). The part that is illogical to a large number of

veterinarians is that, with a snake bite on a small animal, you don’t have a few days for the production

of antibodies. Red Rock Biologics have not demonstrated that the vaccine will stimulate enough

antibodies – and quickly enough to neutralize the venom. “If you do decide to use the vaccine, it’s

important not to develop a false sense of security. Owners need to understand that this vaccine will not

eliminate the need to take the dog for care should he be bitten. It may buy some time to get him to the

veterinarian; then again, it may not. Don’t assume the vaccine will provide any amount of cushion”.

(The Rattlesnake Vaccine for Dogs: Both sides of the Story by Dr. Laci Shaible, 2020)

So, if you have the inclination to let your dog off its leash in the Open Spaces or other wild areas of New

Mexico, remember, that as your dog’s Person, you have the responsibility to look out for their

instinctual behavior. Most city dogs (particularly younger dogs) don’t have “snake training”, but they do

have an insatiable curiosity to checkout basking snakes and will take off with the boundless

enthusiasm/lack of judgement of 2-year-old human hyped on sugar to chase the very same prey as

those hunted by rattlesnakes. The ultimate discussion over prey rights and trespassing can be deadly.

Summary

Rattlesnakes are common in our area. Long an icon of many cultures in the American Southwest, the

rattlesnake and the Western Diamondback in particular, plays an important role in controlling the

rodent population and preventing several nasty diseases from spreading widely. Left on their own they

are reclusive not highly aggressive but, when provoked, will attack quickly and effectively with a

venomous strike. Fortunately for humans the bite is rarely lethal because venom is slower acting than

that of many snakes and it is easily counteracted by a widely available antivenom serum. Full recovery is

common.

last updated 7 April 2021